What is a Power Purchase Agreement (PPA)?

Definition

A Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) is a power offtake agreement between two parties, being a (green) electricity producer and an offtaker of this electricity, such as an electricity consumer or trader. A PPA includes all the terms of the agreement, such as the amount of electricity to be supplied, the negotiated price, who bears what risks, the required accounting, and the penalties if the contract is not honored. As it is a bilateral agreement, a PPA can be adapted to the wishes of the parties involved, so the supply contract can take many forms. Electricity can be supplied directly or virtually via a PPA (see below).

Generally, a PPA is a long-term contract, such as ten or fifteen years. It (partially) removes the risk of fluctuations in the electricity markets, which is desirable for large, debt-financed projects. PPAs are also concluded for the continued operation of renewable energy installations when they no longer receive subsidies.

A growth in the number of PPAs is also visible in Belgium. An example is the PPA that Google concluded with Engie for the supply of offshore wind for its data center.

Why close a PPAs?

Depending on regulations and the energy market, different situations may arise in which PPAs are an advantageous and stable form of energy supply or purchase. Are you a developer or owner of a PV installation or wind farm? Then you need a party that buys the generated power. Or are you a large-scale consumer who would like to be supplied with green power at an attractive rate? Then you can choose to enter into an agreement with a producer of renewable energy, with or without an intermediary who takes care of processes such as program responsibility.

Often, the financial institution providing the loan for the development of a solar or wind park requires that a PPA with a creditworthy purchaser can be submitted. Depending on the size of the park and the duration of its subsidy, they will impose certain conditions on the agreements regarding the risks and duration of the PPA. For projects that are financed by the owner, there is complete freedom to tailor the purchase agreement to the needs and wishes of both parties.

Common types of PPAs

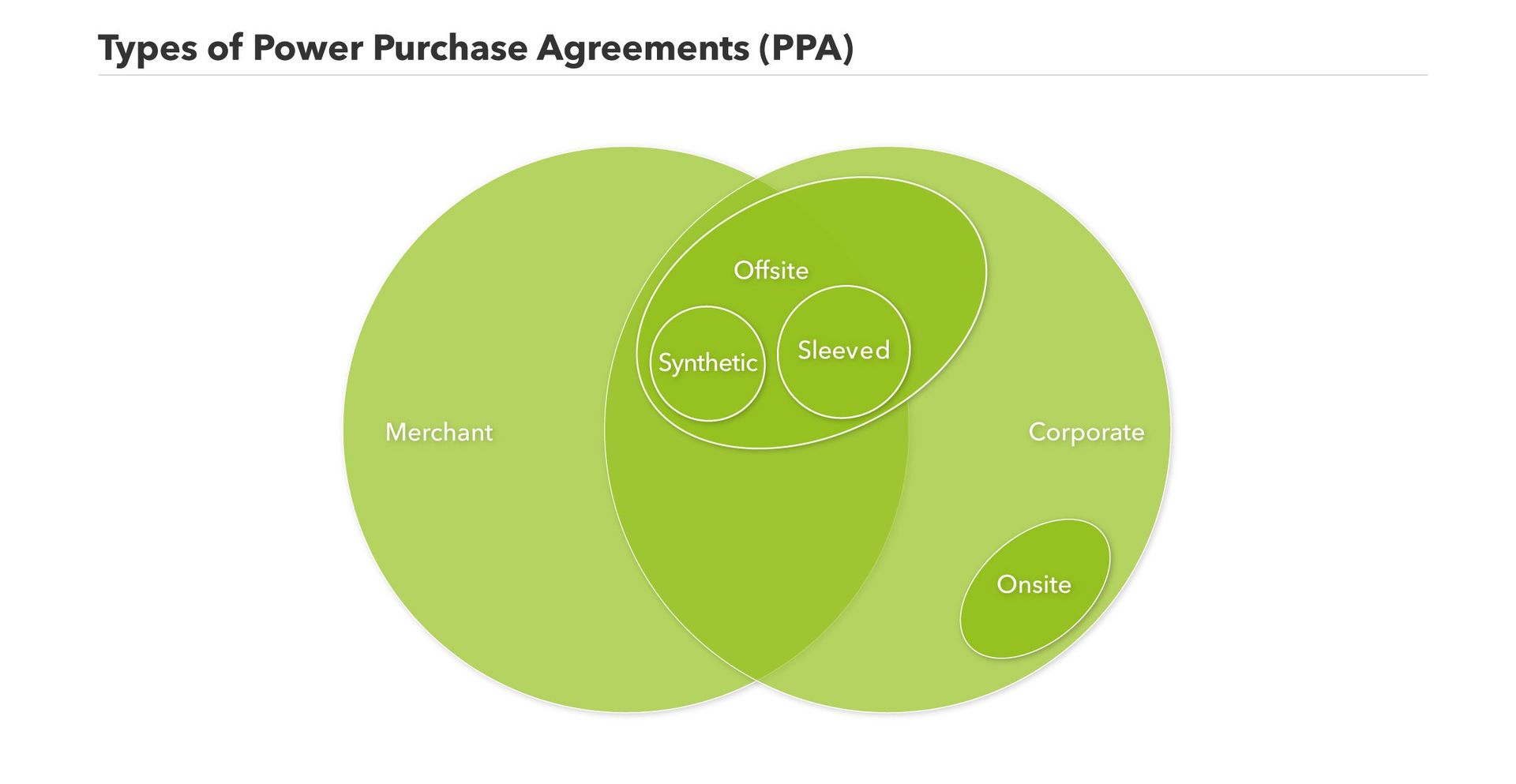

The wide variety of possible contractual arrangements makes it difficult to define the different types of PPAs. We discuss here the most common types of PPAs. On the one hand, a distinction can be made on the basis of the purchaser of the generated electricity (corporate versus merchant), and on the other hand, a distinction can be made on the basis of whether or not the electricity is delivered physically or virtually (physical versus virtual).

Who buys the power?

Renewable energy plant operators conclude PPAs either bilaterally with a (large or industrial) consumer ("Corporate PPA") or with an electricity trader who in turn resells the electricity produced ("Merchant PPA"). Either he does so to a specific electricity consumer (which makes the contract a "Corporate PPA" again) or he trades the electricity on the power exchange.

The Corporate PPA is on the rise internationally. Companies such as Google and Apple have committed themselves to supplying their data centers with green electricity in this way. Reasons for this are stable and thus calculable electricity prices, and the strengthening of their ecological and innovative image. In Belgium, it is still some time before there is a breakthrough: most parks are looking for a customer for 10 to 15 years, which is a very long purchasing contract for a company. Nevertheless, one can expect the number of corporate PPAs to grow in the coming years thanks to the increasing interest among companies in green electricity generated in their own country.

How is power supplied in case of Corporate PPAs?

Either the generated electricity is physically delivered to the purchaser, meaning that it enters the purchaser's balancing group, or the transaction is purely financial or 'virtual'. In the last case, the power does not end up with the purchaser, but in the balancing group of the program responsible party at the generation site, while the volumes are settled financially between the PPA parties.

Physical PPAs

There are three types of physical PPAs, within which some overlap. A common factor is that within these PPAs a fixed quantity of electricity is sold and delivered. The difference lies in the way electricity is delivered.

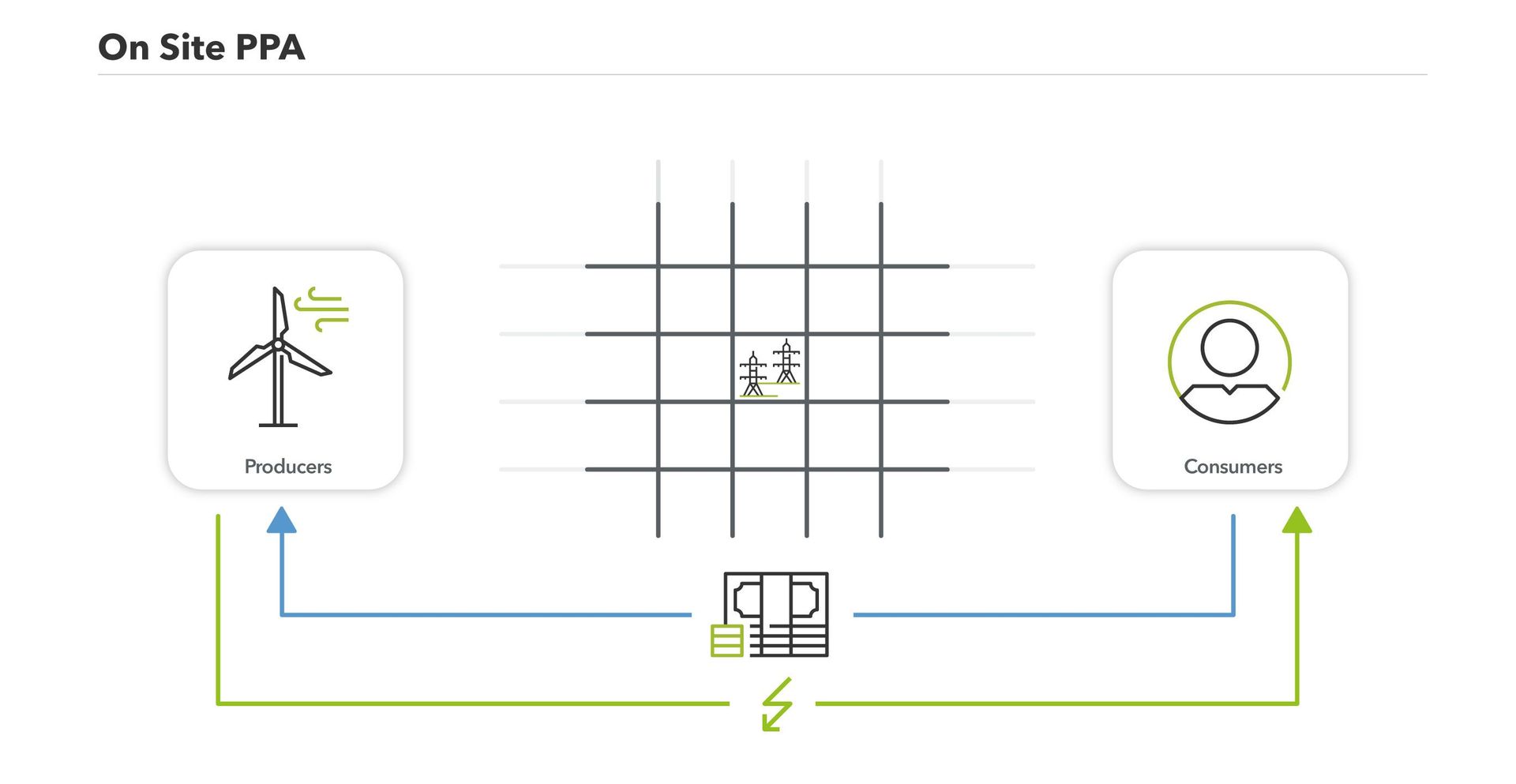

On-site PPA

An on-site Power Purchase Agreement involves the direct physical supply of electricity without using the public grid. In this case, the energy production plant is located behind the consumer's metering point, i.e., for example, on company premises, or there is a direct line between the two. This also means that energy production and consumption are within the same balancing group. With an on-site PPA, grid costs and energy taxes can be reduced. The dimensions of the plant are usually tailored to the consumer's consumption profile. Since the electricity generated in an on-site PPA directly reduces a company's consumption, all on-site PPAs are also Corporate PPAs.

An example: An industrial company has a hall with a roof suitable for a PV system. The company wants to reduce its electricity procurement costs but outsources the development of the photovoltaic system as well as the investment, project and operational risks. In doing so, he can enter an on-site PPA with a project developer who installs and maintains the solar panels on the roof of the hall, whereby the generated electricity is sold to him.

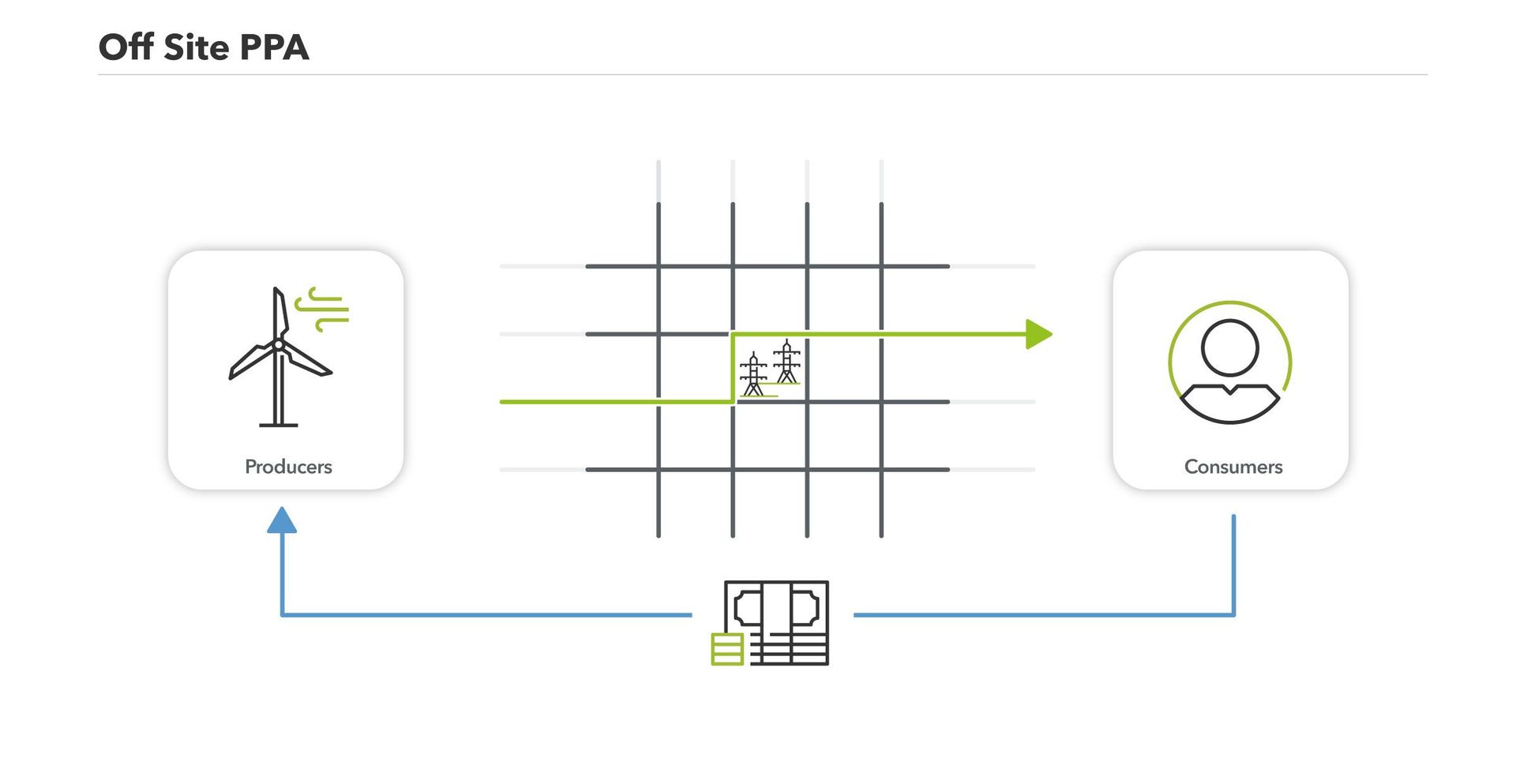

Off-site PPAs

In an off-site PPA, the generated electricity is delivered to the consumer via the public grid. The electricity is not supplied directly to the consumer (the consumer buys the electricity mix from the public grid), there is only an agreement on the purchase of a physical quantity of electricity as defined in the PPA. An additional settlement between the balancing groups of the power plant and the consumer is therefore necessary.

As the generation plant does not have to be installed in the vicinity of the power customer, additional flexibility is created, as the plant operator can now choose locations with optimal conditions or an existing wind or solar plant. A power plant can also conclude multiple PPAs with different customers, who purchase and pay for a part of the electricity production via their balancing groups. In this case, the price for the supply of electricity is fixed in the PPA, giving all participants long-term price certainty. Costs and grid fees are also paid to the grid operator. The Guarantees of Origin generated during the production of electricity can and are usually transferred to the customer.

Example: an industrial company in the port of Antwerp wants to buy green electricity and does not want to be dependent on the energy mix of its energy supplier. The company therefore concludes an off-site PPA with a project developer in the south of the country. The latter is building a wind farm in Estinnes and supplies the contractually agreed quantities of electricity from the total production to the grid. The energy that the industrial company in Antwerp does not obtain from the wind farm is supplied by its energy supplier.

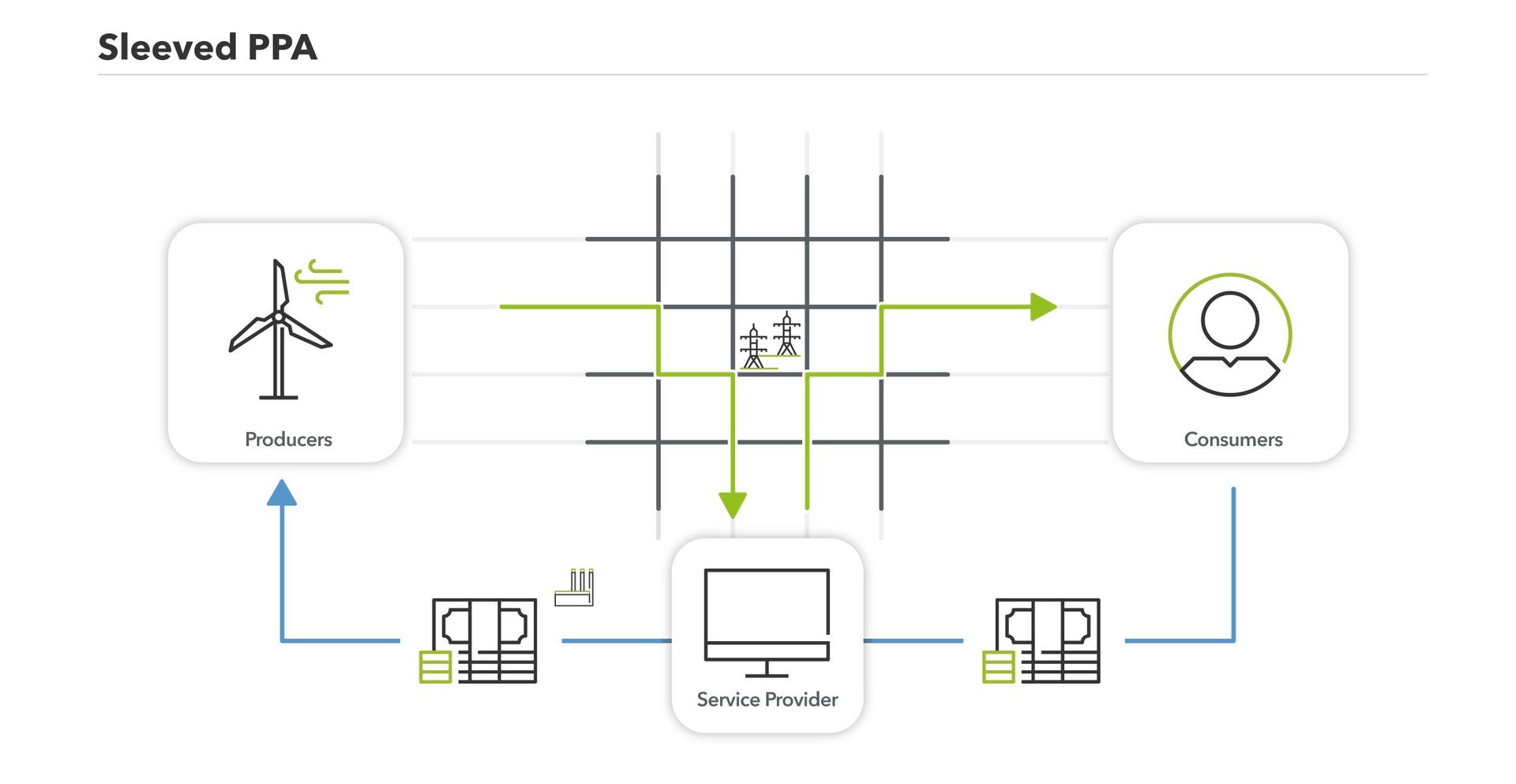

Sleeved PPA

A sleeved PPA is simply an off-site PPA in which an energy service provider takes over various processes and acts as an intermediary between the electricity producer and consumer. For example, this energy service provider assumes the balancing responsibility, combines several electricity producers and/or consumers into one portfolio, delivers or sells the missing or surplus quantities of electricity respectively, provides the forecasts, trades the Guarantees of Origin, or takes over certain risks from the producer and/or customer (such as imbalance, profile or credit risks).

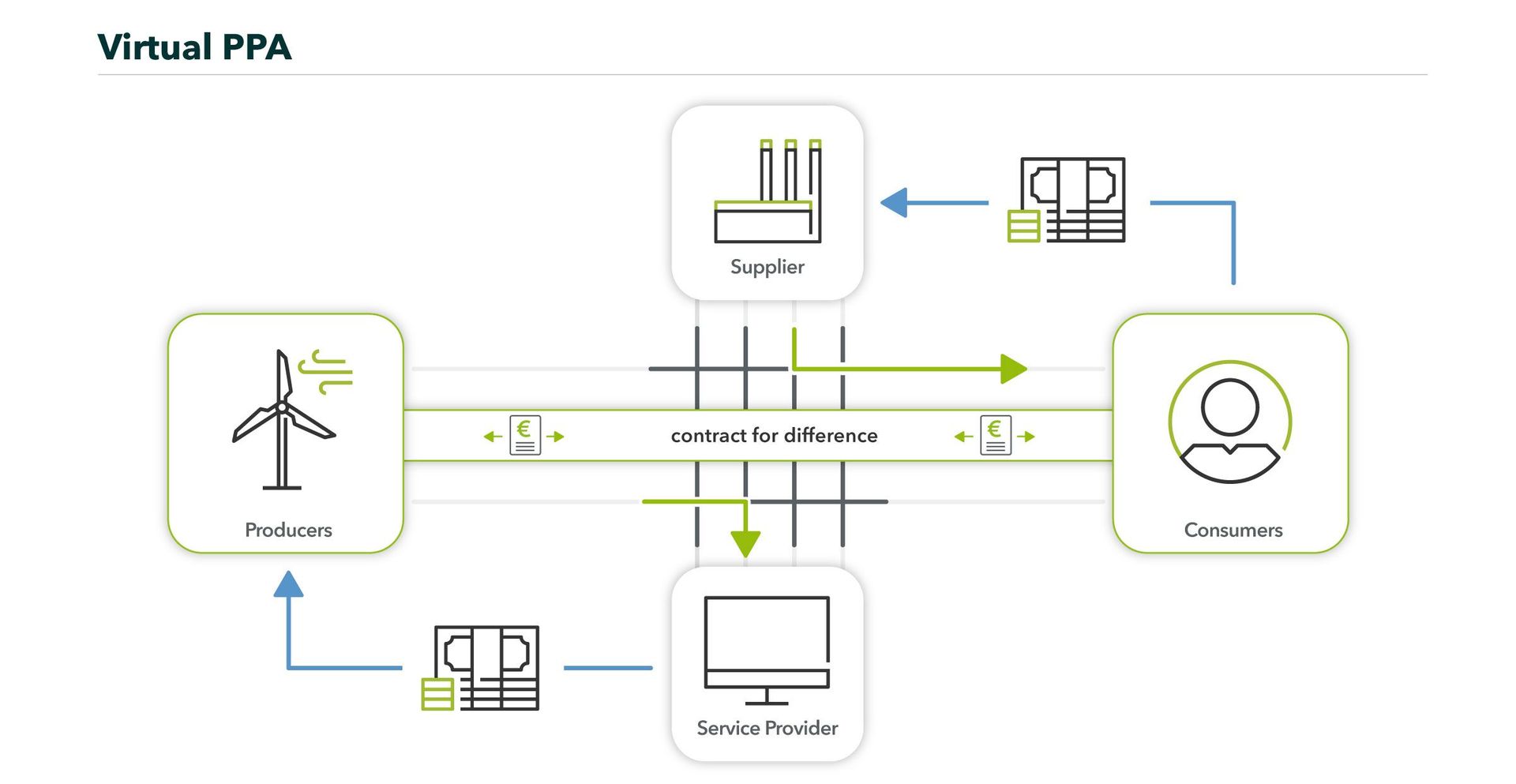

Virtual or synthetic PPAs

Synthetic or virtual PPAs decouple the physical flow of electricity from the financial flow and thus allow for even more flexible contractual arrangements. In the case of synthetic power purchase agreements, generators and consumers agree on a price per kilowatt-hour of electricity, as is the case with physical PPAs. However, the electricity is not delivered to the consumer by the power plant. Instead, the generator's energy service provider (e.g. an electricity trader) takes the produced electricity into its balancing group and trades it, e.g. on the EPEX spot market. The consumer's energy supplier buys for the PPA partner on the consumer side exactly the feed-in profile that the generator has delivered to its energy service provider, e.g. through spot market purchases.

In the synthetic PPA, this electricity flow is now complemented by a so-called Contract for Difference. In this contract, the PPA partners commit to make additional financial compensation payments to the extent that the spot price (paid by the generator to its energy service provider and paid by the consumer to its supplier) differs from their bilaterally agreed price. This means that each PPA contractual partner has two payment streams (once with its energy service provider or supplier and once with the other PPA contractual partner), which are in any case added to the PPA price established at the beginning and thus achieve the desired price certainty on both sides.

By eliminating a direct physical delivery between the contracting parties, as in the case of an on-site PPA, and by eliminating a direct balance connection between the two contracting parties, as in the case of an off-site PPA, this form of PPA is a simple and administratively cheap form of PPA and is therefore suitable, for example, in the event that the power generator does not operate its own balancing group or does not wish to start one.

Advantages and Disadvantages

Advantages of PPA

Risk reduction: PPAs are an effective means of reducing the risk of fluctuations in energy prices, especially for operators of installations with high investment costs (CAPEX) and low operating costs (OPEX) (e.g. PV installations and wind turbines). A project can get off the ground earlier and become profitable because of a constant payment for delivered electricity and trust from the project developer (and its financial backers) that the proceeds from the sale of the electricity will cover the investment costs. In addition, certain risks can be transferred to the offtaker.

Marketing value: PPAs also have a marketing value: physical supply of electricity with certain regional characteristics and the associated guarantees of origin creates opportunities for consumers to make their brand more sustainable and greener.

Flexibility: The openness of the contract design also creates a lot of room to take into account the individual preferences of power plant operators and electricity consumers. This also applies to pricing: PPAs can be concluded at fixed prices or there can be scope for flexibility, allowing for greater participation in market risks and opportunities.

More to read

Disadvantages of PPA

Complex: PPAs are complex contracts which often require a lot of time to agree on the terms. This also makes Corporate PPAs primarily concluded by large companies.

Long duration: As PPAs are traditionally long-term contracts, both parties are bound by long-term conditions. In this case, the financial risk is high: if electricity prices rise, the generator may lose a lot of revenue, if prices fall, the customer loses out.

Variable generation: Furthermore, there are volume and profile risks related to the variable nature of wind and solar energy generation. If the agreed amount of electricity is not available at the time of delivery, the plant operator must be able to compensate for this financially or physically, or outsource it to a third party, such as an electricity trader.

Disclaimer: Next Kraftwerke does not take any responsibility for the completeness, accuracy and actuality of the information provided. This article is for information purposes only and does not replace individual legal advice.